Robert Davy, Emerging Market Equities Fund Manager at Schroders

Simmering social discontent, high unemployment and inequality mean reforms are urgently needed. We look at what this means for South African equities

The imprisonment of former president Jacob Zuma triggered major social unrest in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, Zuma’s home province, in July.

Arterial transport routes linking these regions, which account for around 50% of GDP, were disrupted, while shopping centres and warehouses were attacked and looted. The government responded by deploying the military and the situation has stabilised. Over 300 people died in the violence.

These events emphasise the urgent need for reform in South Africa. The unemployment rate is close to 33%, and even higher among young people, while income inequality is extreme. Under the leadership of President Ramaphosa there has been reform progress, but it has been slow. Economic growth has shown signs of improvement but remains low.

The government response appears to have stabilised the outlook, with transport connections reopened. The fact that the unrest appears to have been coordinated, and that instigators are now under investigation, suggests that stability may be maintained, at least for now. The government has taken measures to provide additional fiscal support, extending a monthly Covid-19 grant to March 2022.

The near-term outlook has not changed in our view. Valuations remains attractive and reform progress is needed. However, the latest events and the risk of further fiscal deterioration only add to long-term structural challenges.

The economy is recovering from the pandemic

South Africa has been experiencing a third wave of Covid-19 over the past few months. This led to the re-imposition of some restriction measures as the domestic alert level was raised to 4, on a scale of 1-5 with 5 being the highest level. With cases now easing the domestic alert was lowered to level 3 at the end of June. The impact on the economy was more limited than in previous waves.

The share of the population who have received at least one dose of the Covid-19 vaccine remains low at 11.6%, as of 8 August 2021. This lags both developed and many emerging market peers. The rollout will open to 18-34-year-olds from 1 September – which could provide a boost to consumer confidence moving towards the end of the year.

The recent resurgence in Covid, together with the ramifications of July’s social unrest, will have a short-term impact, but the economic recovery was already gathering momentum. Q1 GDP growth of 4.6% was stronger than consensus had anticipated. Manufacturing PMI had been in the mid-50s for much of this year, while industrial production was rebounding and retail sales, picking up. Car sales were up 40% over the past six months, albeit they are still 12% below 2019 levels. Commodity price strength has been a further pillar of support for exports.

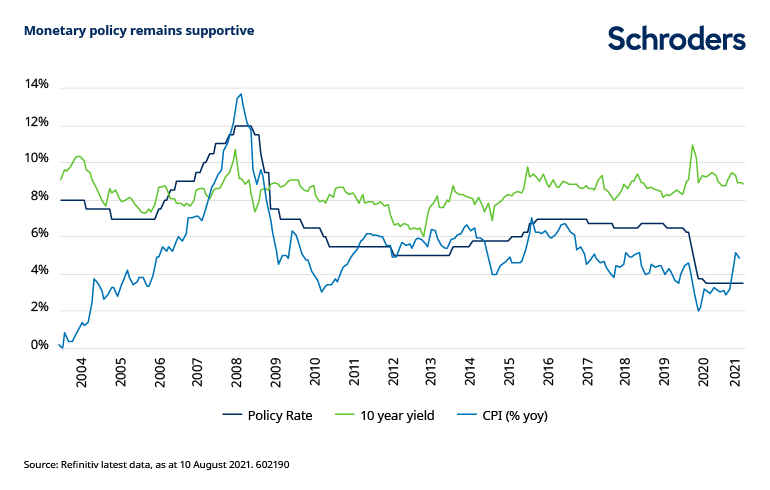

Inflation has picked up, as the chart below shows, with the rebound in demand, higher energy and food prices, as well as the effect of a lower base driving the change. Headline inflation (which includes energy and food prices) could take time to ease given some supply disruption stemming from the social unrest in July. Monetary policy continues to be supportive although there is potential for a 25bps rate hike later this year, should inflation remain elevated.

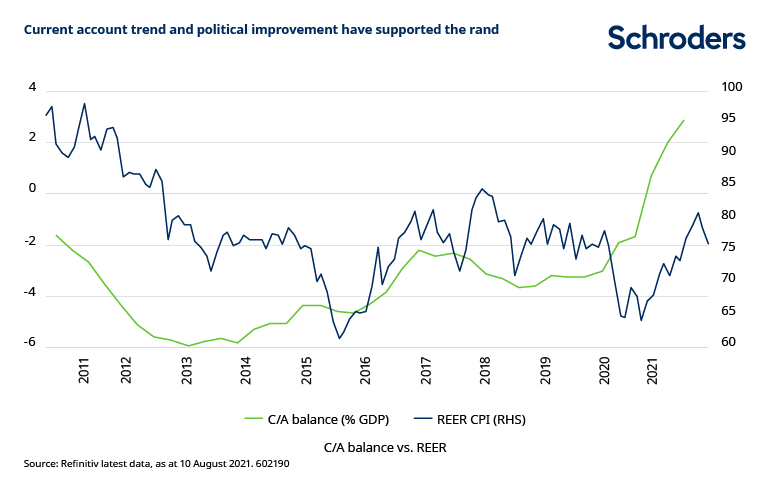

The current account has moved into surplus

South Africa’s economy has been fragile for a number of years due to its twin deficits (fiscal and current account deficits). In the past year, however, the current account has swung to a surplus and fiscal performance has also improved. These factors, together with sequential improvement in the political environment, have supported the rand, as the next chart illustrates.

The Q1 current account surplus was the second-largest since records began in 1960. The improvement over the past 12 months has primarily been driven by the drop in demand for imports as a result of the pandemic, and the strong rally in commodity prices. The surplus may well fall as commodity prices normalise.

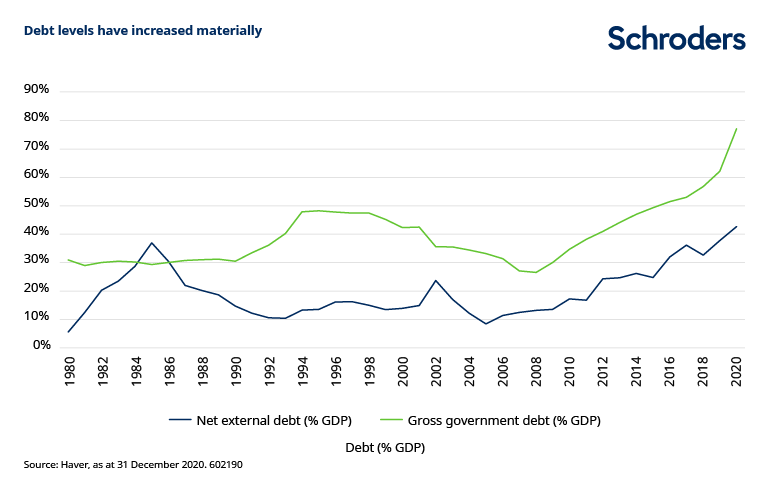

The fiscal challenge remains significant

Public debt levels in South Africa have ballooned over the past 12 years. The Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the problem with the budget deficit rising sharply to -12.3% of GDP in 2020. Gross government debt now sits at close to 80% of GDP. Fiscal reform has been increasingly imperative for some time but is equally difficult to deliver politically.

Under President Ramaphosa, there has been greater reform focus, but the pace of change has been slow, perhaps necessarily so, due to a lack of broad support within the ruling African National Congress Party. The scale of reform required remains significant.

For example, heavily indebted state-owned power company Eskom generates most of the country’s power supply, but poor management and a lack of capital investment over the past ten years have resulted in frequent breakdowns. As a result, the country faces ongoing load shedding or blackouts. Recent reform which allows companies to generate up to 100 times the existing threshold for power generation is incrementally positive but does not resolve the main issue of Eskom’s inability to provide reliable electricity to the economy.

In response to the social unrest, the government has increased an existing Covid-19 grant to March 2022. This is estimated to cost an additional R27 billion. President Ramaphosa is also weighing up the feasibility of introducing a permanent basic income grant. This could add an upside risk to the government debt burden, particularly as commodity prices normalise.

Public sector wage negotiations, which have been ongoing for several months, recently reached an agreement on an effective 5% increase (including monthly cash bonuses). The deal covers the next 12 months, meaning that fresh negotiations will be required in 2022.

The political environment has improved but remains fragile

President Ramaphosa’s position has been strengthened in recent months, with his appointees gaining greater control within the ANC. For example, Secretary-General Ace Magashule, from a more radical faction of the ANC, was suspended earlier this year, pending the outcome of a corruption charge. However, July’s social unrest has cast a shadow over the reform outlook, not least because it will require additional fiscal resources.

President Ramaphosa has moved to reshuffle his cabinet. The key change was the appointment of a new finance minister after Tito Mboweni stepped down. He was replaced by Enoch Godongwana, head of the ANC’s economic transformation committee, who is well known to markets and is closely aligned to President Ramaphosa. Ramaphosa also abolished the security ministry and moved oversight of intelligence to the presidency as well as changing the health minister.

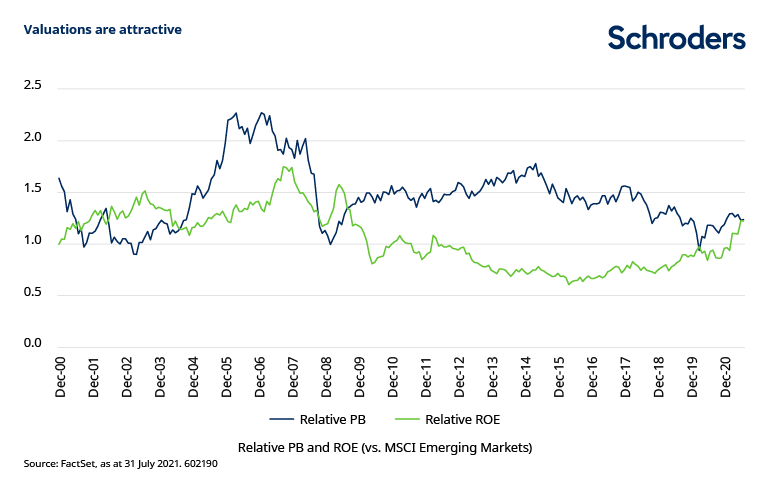

Equity market valuations are attractive

Looking at the equity market, valuations are attractive with the MSCI South Africa Index trading on a forward price-earnings ratio of 9.7x, well below the 12.4x average of the last 15 years, and relative to 13.7x for the broader MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Valuations of domestic stocks, in particular, remain compelling. Although the market is cheap in aggregate, it is important to note that a significant proportion of the MSCI South Africa Index is comprised of cyclical stocks.

Return-on-equity is improving, both in absolute terms and, as the chart below shows, relative to wider emerging markets. We continue to see a recovery in earnings-per-share across a number of sectors. In addition, capital allocation from management teams is improving.

Near-term outlook unchanged, but long-term structural challenges remain

July’s social unrest has not changed our near-term outlook for South Africa. While it will have a short-term impact on the economy, the government’s response has stabilised the situation and growth should continue to recover post-pandemic. Monetary policy remains supportive and there has been an improvement in both the current account and fiscal positions. Equity valuations are attractive, especially among domestic stocks.

However, as the events of July revealed social discontent simmers just beneath the surface; unemployment remains high, as does inequality. The economy faces long-term structural challenges, not least of which is still-low economic growth that is further hampered by an unreliable power supply and significant government debt levels. To address these social challenges and accelerate economic growth, reforms are urgently needed, but progress is slow.

Does social unrest change South Africa’s outlook?