Adam Bulkin, Head of manager research at Sanlam Multi-Manager International

For South African investors considering offshore investing, there are many choices to make, the implications of which are extremely far-reaching. These include what portion of assets to keep in domestic assets and what in offshore assets, which asset classes to invest in and how to gain exposure to these asset classes (for example using passive index-trackers or active managers).

Global markets are more developed, complex, specialised and varied than the South African market. So, to make optimal investment decisions, investors require a great breadth and depth of knowledge. Since each investment choice has the potential to create high variability in an investor’s returns (for example as currencies fluctuate quite widely over time), these choices should be made intentionally, unemotionally, and with a clear, well-articulated rationale.

In addition to the variability of foreign exchange and asset class returns, there is also variability within asset classes, driven by factors such as styles, sector and regional allocations. While asset allocation skill, including the division between onshore and offshore assets, is extremely important, so is security selection skill within pertinent offshore asset classes. Strategic versus tactical considerations are also a critical considerations.

In our view, given this background, the ideal investment framework for global investing requires strategic and tactical asset allocation and the ability to select asset managers that have expertise and skill in their areas of specialisation.

Along with the requirement to understand an investor’s objectives and requirements, it is also essential for an adviser to consider such an investor’s local and offshore investments in an integrated and holistic manner, because the correlations and anticipated behaviour of different local and offshore assets in various scenarios is a critical element of optimal portfolio construction. This may mean that a South African investor could, for example, have a high allocation to local cash while also maintaining a high allocation to offshore equities, because he or she wishes to have exposure to growth assets (such as global stocks) but also to enjoy some protection should such assets suffer a severe loss in a global risk-off environment.

In considering this scenario, it is worth noting that equity investment returns are determined by three major components:

- Dividend yield;

- Earnings growth; and

- Rating changes (changes in price multiples, such as price to earnings).

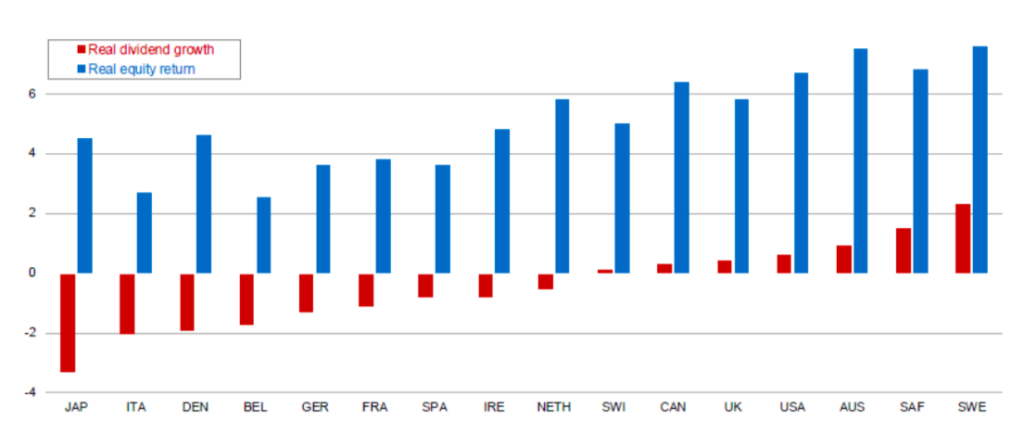

History supports the conclusion that growth matters. The graph below, sourced from Sanlam Investment Management (SIM) shows the cumulative dividend growth and equity return data for the previous century for 16 countries for which data was available for such a long period.

This shows that, generally, higher growth results in higher returns. Where there are deviations from this, such as Japan (and to a lesser extent Denmark), the deviations are explained by excessive pricing anomalies that still existed at the end of the time period used for compiling this summary (i.e. at the end of the previous century), for example, the Japanese stock market bubble of the 1980s.

Earnings growth, at the aggregate level, is driven mainly by:

- Economic growth – i.e. does the economy provide an environment within which companies can deliver growth?

- The ability of companies to sell products beyond the borders of their domestic economy.

- Scalability of a market’s product set.

It is worth considering whether South Africa’s economic growth will be superior to that of other countries in the future, given the estimates of a long-term growth rate in South Africa of approximately 2% or below – inferior to that of the global average – limited by a combination of well-known structural issues. It’s also interesting to compare South Africa’s portion of global growth to that of the world – SA contributes just 0.4% to global GDP, while the JSE market cap is only about 2% of that of the MSCI ACWI (all country world index).

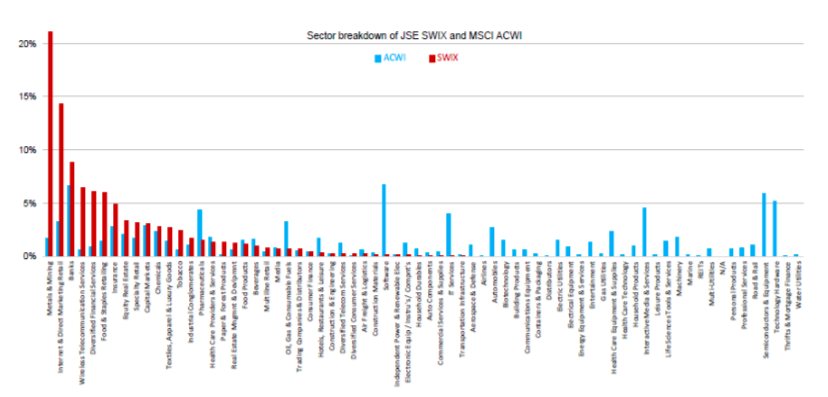

The graph below, from SIM, illustrates the breadth of markets and compares the composition of the local equity market’s SWIX index to that of the MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI). The breakdown used is the main sector classification of the MSCI ACWI. It clearly highlights the very concentrated nature of the local market, with much of this concentration in the “old economy sectors” of resources, financial services and retailers. It is also quite sobering to note that should one expand this to the sub-sector level, the ACWI has more sub-sectors ****than the number of individual counters ****in the SWIX!

South Africa’s equity market is not only concentrated by sector, but is also highly concentrated by an individual counter, and lacks depth – in many sectors, South African investors are predominantly limited to a single large company (e.g. Sasol, Naspers, Richemont, etc. in their respective sectors). Thus, company diversification within sectors is severely limited.

This does not mean that South African stocks will not present compelling opportunities from time to time, based on valuation and earnings growth prospects over the shorter term, driven particularly by commodity prices. Nevertheless, if we consider these various aspects – the low probability of SA companies achieving superior earnings growth to the rest of the globe, at least over the longer term; the breadth and depth of global equity markets compared to the local equity market, etc. We think that there is a strong case to be made for a strategic exposure to global equities within a South African investor’s allocation to growth assets.