Earl van Zyl, head of product development at Allan Gray

Retirement and local unit trust investors are now able to allocate up to 45% of their portfolios anywhere outside South Africa, from the previous offshore limits that allowed 30% outside Africa, plus 10% in Africa excluding South Africa (“ex-SA”), for a theoretical maximum of 40%. While the increase in the total allowed outside South Africa on paper is only five percentage points, in reality, most investors previously held less than 5% in Africa ex-SA. In practice, the recent change will mean that most investors can now invest an additional 50% of their portfolio offshore.

How much should one invest offshore?

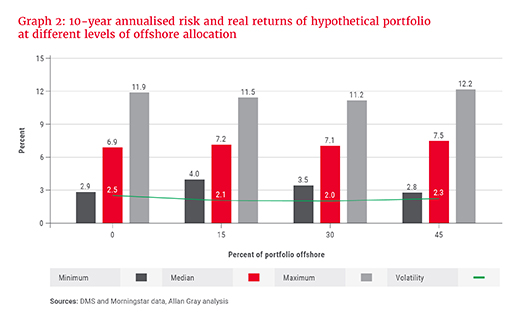

As with most questions in investing, the answer depends on your personal circumstances, risk appetite and required real return. For simplicity, we will illustrate the factors to consider, and the trade-offs to be made, using a simplified but representative multi-asset portfolio blends of 60% in equities and 40% in bonds, which would have delivered 10-year annualised real returns of 6.9% on average over the last 30 years if invested entirely in South African assets. We will assume that as the portfolio allocates more offshore, there is an equal allocation between equities and bonds offshore – that is, 30% offshore means that 30% of the equity portfolio and 30% of the bond portfolio is invested offshore.

Graph 2 illustrates that allocating a higher proportion of one’s portfolio offshore has a meaningful impact on the expected outcome of that portfolio in a number of ways. Firstly, the volatility of long-term returns of the portfolio reduces as one increases the offshore allocation from 0% to 30%, and increases again at an allocation of 45%. Secondly, the average 10-year returns available from the hypothetical portfolio increase with increasing levels of offshore allocation, although perhaps less than one might have expected given the underperformance of South African equities in the recent past. Finally, the range of return outcomes narrows at offshore allocations between 15% to 30% but is higher both at 0% offshore as well as at 45% offshore.

These results indicate that offshore investing is not a simple matter of maximising your allocation to offshore assets. Rather, there are trade-offs that investors need to weigh up to determine what allocation best meets their investment goals and appetite for risk.

Graph 2: 10-year annualised risk and real returns of the hypothetical portfolio at different levels of offshore allocation

Sources: DMS and Morningstar data, Allan Gray analysis

Some may argue that negative excess returns of South African equities versus global equities over the last five years suggest that our simplified model is flawed; that perhaps South African investors should be using most of their offshore allocation for equities, rather than a similar blend of equities and bonds to the local component, especially as expected real returns from South African bonds today are extremely attractive in absolute terms and relative to global bonds. However, this argument would be dangerously reliant on the next 10 years looking like the last 10.

Conclusion

In managing Allan Gray’s Equity, Balanced and Stable unit trusts, our investment team continues to assess this question, as they always have. We have been saying for some time that South African assets currently offer better value than many of their offshore counterparts, so we are not allocating more offshore simply because the regulations allow us to do so. Instead, our portfolio managers continue to make decisions about the level of offshore exposure according to our assessment of where the best value can be found over the long term. Investing in an asset allocation fund that is appropriate for your risk appetite can take the pressure off you having to make your own decisions in this regard.