Izak Odendaal and Dave Mohr, Old Mutual Wealth Investment Strategist

Izak Odendaal

Dave Mohr

Inflation is still very much in focus globally. Investors are nervous that sharply higher inflation will put pressure on central banks to raise interest rates, potentially knocking the global economy and short-circuiting equity markets.

After a strong run, most global equity indices pulled back in recent days as risk aversion increased. This despite most US and European companies reporting unexpectedly strong earnings growth. Of course, markets never move up in a straight line, so a correction every now and then should not by itself be cause for concern. Rather, the question should be whether something fundamental has changed, causing a complete repricing of the outlook. As discussed further below, that does not seem to be the case. Last week the spotlight also turned to domestic inflation, its future trajectory and interest rate implications.

South Africa’s consumer price index rose 4.4% in April from a year ago, slightly faster than expected by economists. This is quite a jump from March’s 3.2%, but not a surprise since base effects play a big role. Fuel prices were 21% higher than a year ago, largely reflecting the fact that global oil prices slumped in April 2020 and have since returned to pre-pandemic levels. Food prices were also 6.7% higher than a year ago, reflecting global food price increases. A big monthly increase in oil and fats cannot be blamed on base effects, however.

Though food inflation is at its highest level since mid-2017, the outlook is fortunately better. South Africa was recovering from severe drought conditions then, whereas bumper harvests should offset the impact of sharply higher global food prices. The firmer exchange rate also helps to ease price pressures. The big drought in 2015/16 coincided with a weak rand, which compounded the misery as South Africa was forced to switch from being a food exporter to importer.

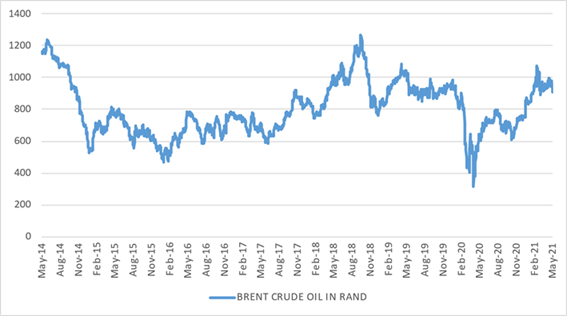

The rand traded around R14 per dollar last week, despite the increase in global risk aversion. It means the increase in global oil prices over the past few months has basically been neutralised, and no petrol price increase is expected for May. It also limits the impact of rising global inflation more broadly. Over the last year, the rand appreciated 20% on a trade-weighted basis, and 8% over the past six months. It is basically flat on a two-year view.

Chart 1: Oil price in rand

Refinitiv Datastream

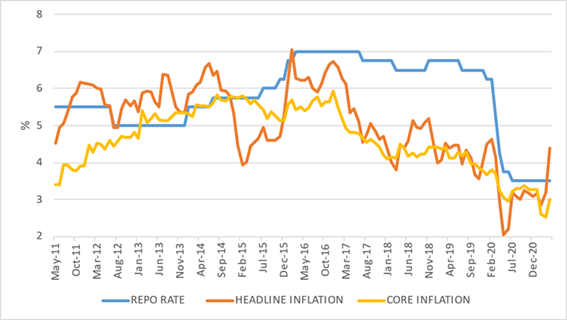

Core inflation, which excludes the impact of volatile food and fuel prices, was at 3% year-on-year in April, off the record low posted the previous month. This suggests that the underlying inflation trajectory has probably bottomed out as the negative impact of Covid-19 on items such as clothing, medical services (regular medical check-ups) and restaurant visits eases up.

Repo rate unchanged

Against this backdrop, the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) unanimously decided to leave the repo rate unchanged at 3.75% as expected.

The Reserve Bank expects inflation to average 4.2% this year, 4.4% next year and 4.5% in 2023. This compares favorably with the Bank’s 4.5% inflation target. It noted that the relatively strong exchange rate would counter global price increases, while a lack of pricing power on the part of firms and bargaining power on the part of unions (both a consequence of an economy still not running at full steam) will contain the inflationary pressures stemming from food prices and electricity tariffs.

However, it noted that its forecasts are more likely to underestimate than overestimate inflation (The risks to the inflation outlook are to the upside, in central banking speak.) One of the items on its list of potential risks is higher import tariffs as a result of the government’s policy to encourage more domestic production. Tariffs typically only have a one-off impact on inflation (similar to a VAT increase), but it depends to what extent firms can pass costs on to consumers.

Chart 2: SA repo rate and inflation, %

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

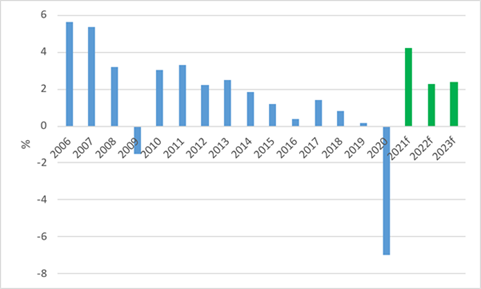

In terms of real economic growth, the Reserve Bank upgraded its growth forecast for 2020 to 4.2%, though of course the impact of a possible third wave of Covid-19 infections is uncertain. Growth for the following two years is still expected to be above 2%. It is worth noting again that local economic growth averaged only 0.5% in the five years before the pandemic, so while 2% average growth over the medium term does not sound impressive, it will be a huge improvement.

Overall, the MPC statement was not particularly hawkish. Like its global peers, the MPC is cognisant of inflation risks but also recognises that the economy still needs plenty of support and will take time to return to pre-pandemic levels of activity and employment.

The Bank’s forecast model suggests two rate increases of 25 basis points each this year, but the MPC has not always followed this guidance and is unlikely to in this instance. Barring any dramatic changes, rates should remain at current levels for the rest of the year. As average inflation rises towards the midpoint next year, the real repo rate will turn negative, which is not something that has historically sat well with the MPC. Rates should therefore rise gradually from next year on if the SARB’s projections materialise.

The global picture

The MPC always pays close attention to the direction of monetary policy in the rest of the world, especially the US, and with good reason. An abrupt shift in the US Federal Reserve’s policy could provoke capital flight, putting upward pressure on long-term interest rates and downward pressure on the rand. A weaker rand in turn can lead to higher inflation, though this impact (or pass-through) has declined significantly over time.

Chart 3: SA repo rate and inflation, %

It helps greatly that South Africa is currently running a current account surplus and is not as vulnerable to capital outflows. In contrast, South Africa was running a massive 6% of GDP current account deficit the last time there was an unexpected major shift in market perceptions of Fed policy, the infamous 2013 ‘taper tantrum’. The Reserve Bank expects a current account surplus of 2% of GDP in 2021, shifting to a modest 0.6% deficit next year.

The Fed’s public messaging has been clear: we don’t expect the inflation surge to last, and we want to be sure the recovery is on a sustained footing before making any changes to the bond buying programme or interest rates. Minutes from the most recent policy meeting suggest Fed officials are starting to wonder whether the time to start considering making changes is drawing closer. Or to paraphrase an earlier comment from Jerome Powell, that it is time to start thinking about removing the emergency support measures.

That day will inevitably come, and the next month or so will provide important data points to guide the decision. Markets will constantly price in these expectations. Things can therefore be choppy for the next while as both investors and central banks assess the situation. However, we need to remember four things.

Firstly, while central banks are not in the business of bailing out markets (their official targets are typically inflation and unemployment), they are nonetheless very sensitive to market movements, since financial markets are key channels through which their policies impact the real economy. They will therefore be very careful not to pull the rug out from under markets, but rather signal their intentions as clearly as they possibly can.

Secondly, central banks, the Fed in particular, have learnt the lessons of the past decade on overdoing interest rate hikes. They will probably err on the side of caution.

Thirdly, it matters why they are tightening policy. If it is because they see their economies as substantially healed and no longer in need of emergency support, it is a good sign. Hiking in response to sustained higher-than-expected inflation is a different matter.

Four, some investments are very sensitive to higher interest rates, either directly or indirectly. But others are more likely to respond positively to the stronger economic growth conditions that give rise to higher rates. It will become increasingly important to distinguish between the two. Clearly developed market bonds and similar ‘duration’ assets (like technology companies whose earnings growth prospects are far into the future) will be harmed, but cyclical companies such as banks, miners and industrials can benefit.

The most likely path of global inflation is still, in our view, that it will moderate going into next year. Firstly, the base effects will fade. To use a simple example, the oil price rose 80% over the past year as it recovered from bombed-out levels. It is not going to rise another 80%. If it stays around current levels of $65 per barrel for the next 12 months, oil inflation will be close to 0%.

Secondly, the big reopening boom is likely to be fairly short-lived. People are desperate to travel and visit fancy restaurants and watch live sports and so on, but there is a limit to how much they do even once it is safe. People are not going to eat in restaurants seven days a week, for instance. The pent-up demand is mainly for services. On the goods side, people have been consuming all the way through the pandemic.

Thirdly, supply will eventually respond. If there is a massive demand for something anywhere, firms everywhere across the global have every incentive to meet that demand as soon as possible. To use an example from a recent Wall Street Journal article, a year or so ago, getting hold of a bottle of hand sanitiser was difficult across the globe. Today the world is awash in hand sanitiser, and retailers are running promotions to clear shelf space for other items. Supply responded to demand. For some items, the response is slow. Increasing food supply is weather dependent and increasing the output of minerals and metals often requires expanding mines. Therefore, the prices of raw materials can remain elevated for some time. But that is not the same as inflation.

Finally, technology remains a disinflationary force. And while it may be too soon to tell if it is the start of a trend, productivity growth seems to be making a comeback. For instance, US productivity growth hit a decade high of 4% in the first quarter. Productivity growth means firms can absorb higher input costs – wages and raw materials – without it leading to higher inflation.

Investment implications

The first and most obvious point is that money market returns will be close to zero in real terms over the medium term since they are closely linked to the repo rate. This is in contrast to the generous positive real returns in the pre-pandemic years. However, if inflation is to be around 4.5% over the medium term, it is a very achievable hurdle for other asset classes to achieve.

A very simple metric is the starting yield, which is around 6% for SA equities (forward earnings yield), 9% for SA bonds (10-year government bond yield) and 9% for SA property. All are well above inflation. Global investments are not quite as attractive from a starting valuation point of view, and fixed income in the developed world remains outright expensive. But offshore investments remain an important diversifier to SA-specific risks, as well as sources of returns not available locally.