Thalia Petousis, portfolio manager at Allan Gray

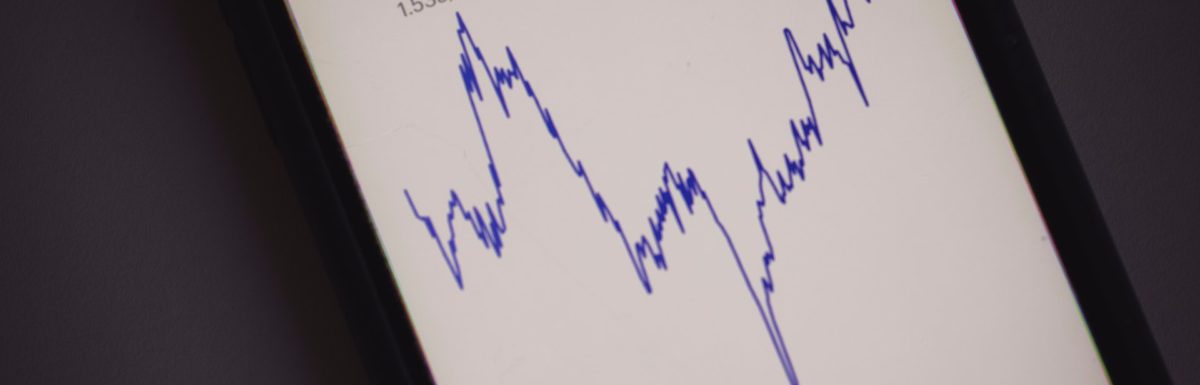

During a brief 48-hour window in late September 2022, a slew of central banks acted to raise interest rates in excess of a combined 600 basis points (6%) across the world – namely Sweden (+1%), the US (+0.75%), the Philippines (+0.5%), Indonesia (+0.5%), Taiwan (+0.125%), Switzerland (+0.75%), Norway (+0.5%), England (+0.5%), Vietnam (+1%) and South Africa (+0.75%).

These central banks are attempting to kill the monster of inflation – ironically one of their own creation. Like Frankenstein’s monster, they claimed that its original conception was for the service and betterment of mankind.

But will the rate hikes work?

One concern is that once given life, pricing feedback loops can run amok, leading inflation to become deeply entrenched in the global economy. Simply put, high prices beget higher prices.

By way of example, she explains that the cost of war and geopolitical tensions are often paid for with inflation, but inflation, in and of itself, has the knock-on impact of (circularly) creating great public and political upheaval. Similarly, what can start as a supply-side energy shock and a rise in fuel prices can also (circularly) be fed by the resulting worker outcry for higher wages. Wage growth has already risen to the realm of 5% to 7% year-on-year across the US and Europe with anecdotal evidence of a shortage of skilled workers. This is known as the wage-price spiral – a feared “second-round effect” of an initial shock to prices.

Back home, in September, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) raised the overnight repo rate to 6.25% to do battle with an August consumer price inflation print of 7.6% year-on-year.

Although the local consumer is weak, and the reported unemployment rate stands at 34% of the ‘official’ workforce, the SARB is alive to the possibility of our own wage-price spiral as public sector unions continue to demand above-inflation wage increases while their workers go on strike.

The SARB is also acutely aware that it must act in line with offshore central banks to protect the value of the rand, which had already lost 19% of its value against the US dollar in the 12 months to 30 September 2022.

Such rand weakness naturally feeds into imported cost inflation, often with a lag. This is a pressing issue given that South Africa swung into a current account deficit in the second quarter of 2022, in part due to large dividend payments to foreign investors. The deficit is also being negatively affected by the rising cost of (imported) oil and fuel. Our exported commodity basket is starting to falter in terms of price momentum and volumes.

The South African forward rates market is still pricing for aggressive interest rate hikes, which has raised the attractiveness of money market instruments as the rate on one-year deposits is now close to 8.5%.

The market is broadly expecting the repo rate to return to the 7% levels last seen in 2016 to 2017.