Keith Wade, Chief Economist & Strategist at Schroders

Schroders chief economist Keith Wade gives his views on the outlook for the global economy in 2022 when growth is expected to cool after a very strong 2021.

The emergence of the Omicron Covid variant has reminded us of the uncertainties which remain around the global pandemic. Despite these, we expect 2022 to be another good year for growth as the global economy continues its recovery. We do, however, see growth cooling following an exceptionally strong 2021, as the massive support offered by governments and central banks during the pandemic’s initial stages begins to fade.

Inflation should moderate, but policymakers and investors face a difficult period in the interim. Our forecast is for 2021 global GDP growth of 5.6% to be followed by 4.0% growth in 2022. We see global inflation at 3.4% for 2021 and rising to 3.8% in 2022.

The economic recovery following the pandemic has differed from economic recoveries of the past. This has thrown up unanticipated problems in supply chains that have been beset by bottlenecks. We’ve also seen issues with labour markets, where companies have struggled with worker shortages. Bottlenecks and shortages have pushed inflation and wage rates higher than expected.

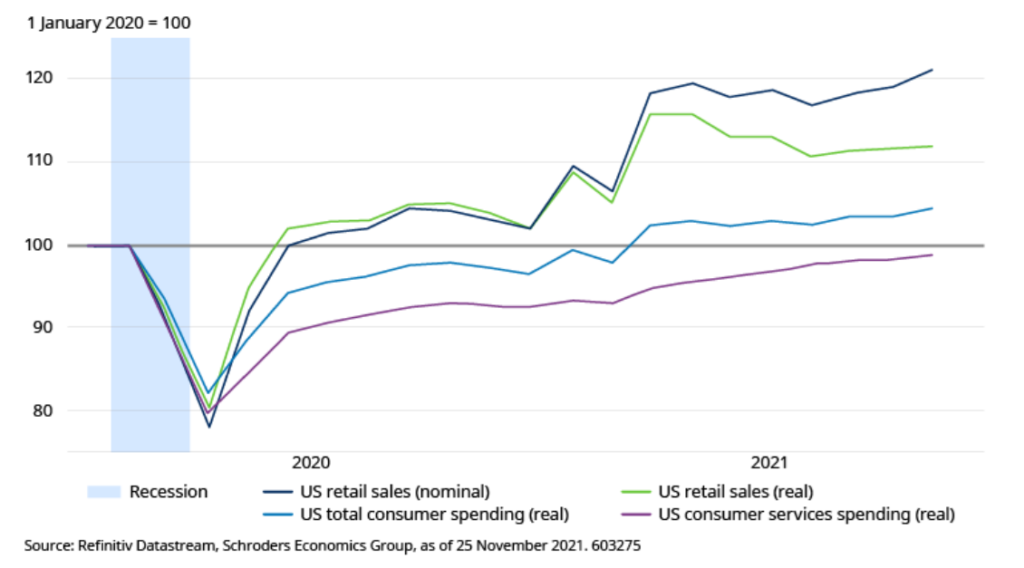

The unbalanced nature of the recovery can be seen in figures tracking the spending patterns of the highly important US consumer (see chart 1). These show that retail sales volumes, or real retail sales, are now more than 10% above their pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, real service sector spending remains some 2% short where it was before Covid-19.

The recovery has disproportionately been driven by the goods sector and this has created extraordinary pressure on supply chains and commodity markets. It took four and a half years for retail sales volumes to surpass previous levels by this degree after the Global Financial Crisis had ended in 2009. On this occasion, it has taken 18 months.

Chart 1: The US consumer recovery

The impact of bottlenecks is apparent in the recent loss of momentum in retail sales volumes. This loss primarily reflects the impact of higher inflation as retailers faced with restricted supply have succeeded in passing on their own cost increases. In nominal terms, sales have continued to forge ahead and are some 20% above pre-pandemic levels.

Higher inflation reflects an imbalance between restricted supply and strong demand. Whilst central banks cannot affect the former (speed the delivery of cargo, say, or, in the case of renewable energy, make the wind blow harder), they can restore balance given they have the tools to address the strength of demand.

Policy support fades in 2022

We expect the withdrawal of emergency levels of support by central banks and governments to play an important role in shaping economic activity in 2022. The massive fiscal stimulus policies (government spending and taxation policies designed to support economies over the short term) in response to the pandemic are already winding down in the US and UK.

Although government spending will remain strong, overall fiscal policy will be less supportive in 2022. This should not be a surprise after the “shock and awe” fiscal largesse of 2021. In the US the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal will start up next year and the larger Build Back Better package currently winding through Congress should help (if it gets through the Senate). The overall “growth impulse” from fiscal policy however will be less than in 2021.

It’s a similar story in the UK where corporate and income taxes are set to rise next year along with higher National Insurance Contributions (payroll taxes).

In contrast, the eurozone stands out as fiscal spending is expected to remain strong due to Europe’s recovery plan. Stimulus is slightly less than in 2021, but still significant. Meanwhile, China is expected to keep fiscal stimulus going in 2022 through higher local government borrowing, but some of it will be due to banks being encouraged to lend more.

With regards to monetary support (short-term policies by central banks designed to stimulate economies), we also see a move in a less positive direction in the US and UK. Here central banks are ending pandemic related quantitative easing (QE) programmes that have been used to inject money directly into the financial system. The Bank of England (BoE) and US Federal Reserve (Fed) are also poised to raise interest rates.

We expect the BoE to raise rates in December 2021 (when the bank’s Covid-era QE programme is also on course to reach its full size) and February 2022. Meanwhile, a patient Fed is expected to raise rates in December next year after fully tapering asset purchases in June (these asset purchases are the means by which many central banks have injected money into the financial system under QE). We then expect interest rates in both economies to rise further in 2023.

Our judgment is that central bank policy goes from positive to neutral (rather than negative) as interest rates are still low relative to the “equilibrium” rate. When an economy is at full capacity this is the rate required in order to avoid either overstimulation (and possibly undue inflationary pressures) or under-stimulation (possibly resulting in economic contraction and the risk of deflation).

Private demand to step up?

These changes should not be surprising as support had to come to an end once the recovery had taken hold. However, for growth to be maintained we need to see a hand-off from governments and central banks to the private sector.

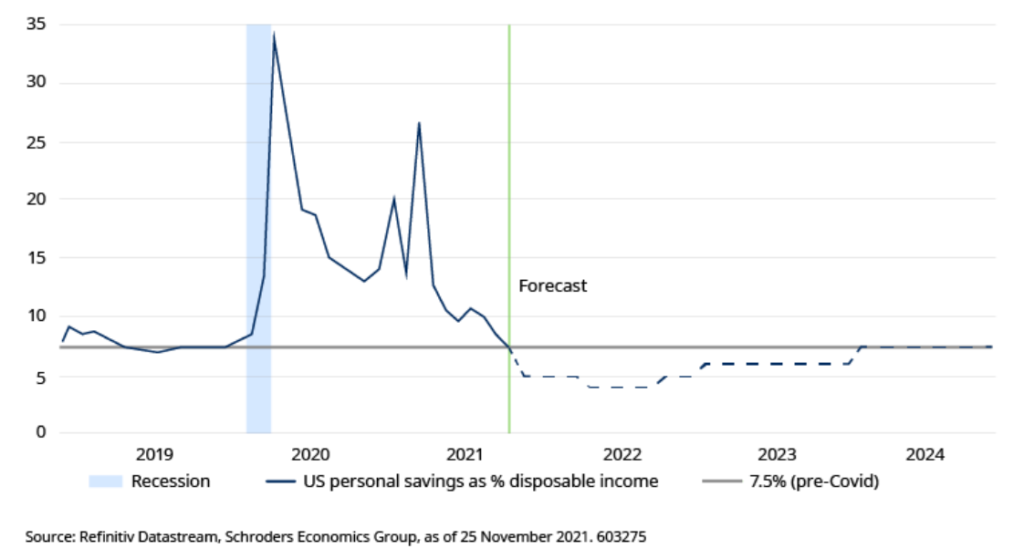

On this front the consumer is critical and here we are looking for households to spend the savings they accumulated during lockdowns. In practice, this would mean a fall in the savings ratio below its pre-pandemic average of 7.5% as excess savings are spent (see chart 2, below).

Chart 2: US savings rate (actual and projected)

The US savings rate has already fallen significantly in 2021, but it is critical for consumption that it continues to decline in 2022. This is because of the squeeze on real earnings from higher inflation, albeit we expect US and global inflation to moderate in the second half of next year.

The story in the eurozone and UK is similar although we estimate that households in these economies are at an earlier stage in running down their excess savings. Judging the situation in China is more difficult due to a lack of data, but it’s believed there are less excess savings than in the West.

Divergent policy outcomes

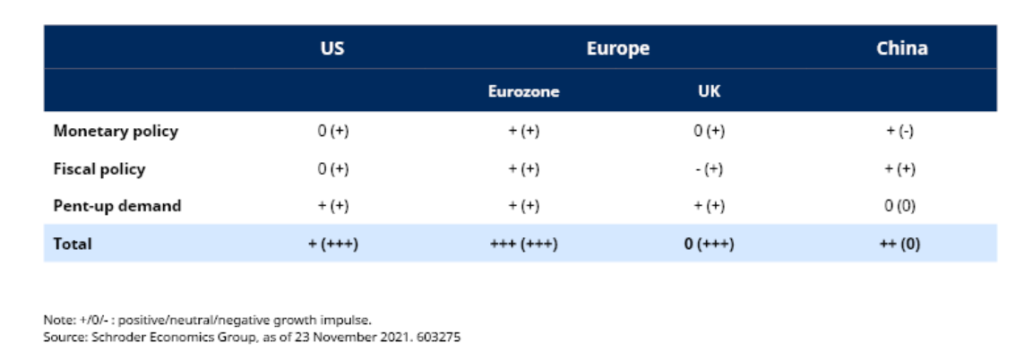

For each of the main economic blocs, we have scored the different components of monetary and fiscal policy and the potential for pent-up demand. On this basis, we see considerable swings between 2021 and 2022 for the US and UK, from maximum stimulus to a more modest or neutral stance. The eurozone remains more full on, while China swings toward more stimulus on both the monetary and fiscal side (see table, below).

We expect the divergence between the US/UK and eurozone/China will create opportunities in bond and foreign exchange markets. We also note many uncertainties around inflation and growth, not least those resulting from supply chain bottlenecks and labour shortages persisting. Higher wage growth feeding through into costs and prices could result in higher-than-expected inflation and weaker growth, at risk of a “stagflationary” outcome.

Growth scoreboard – 2022 (versus 2021)

The emergence of the Omicron variant occurred after we finalised our forecasts, but clearly increases the risk of new restrictions on activity and renewed supply side disruption.

At this stage, it is too uncertain to judge the macro impact, only that it adds to the stagflationary risks in the world economy.