Old Mutual Investment Group’s Investment Strategists Izak Odendaal and Dave Mohr

It was never going to be pretty. Investors braced themselves for bad news from the Finance Minister’s Supplementary Budget, and bad news is what they got.

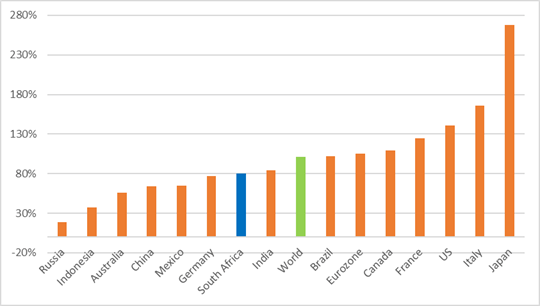

But there are some silver linings. Before getting to the specifics, it is important to note that public debt levels are soaring across the world as governments spend to support their economies and health systems while tax revenue is plummeting. And because economic activity has declined, the ratio of public debt to national income (GDP) is increased by both the denominator and the numerator. The International Monetary Fund’s updated forecasts show that global growth will be even worse than thought as recently as April (-4.9% vs -3%). It expects global public debt ratios to hit record highs, eclipsing even World War II levels.

Chart 1: Projected 2020 government gross debt for selected countries, % of GDP

Source: International Monetary Fund

South Africa is somewhat unique in that we came into the Covid-19 crisis with a large budget deficit as government spending was much higher than tax revenue, a gap the Minister likens to the jaws of a yawning hippo. The second problem is that we came into this crisis with high borrowing costs (government bond yields). While developed countries saw their bond yields fall to such low record levels that new long-term borrowing is essentially free, South Africa still pays a steep price for any new borrowing. Ironically, it is partly because the market is worried about unsustainable debt levels that our yields are so high. Talk about a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A bridge too far?

The Minister called the Supplementary Budget a “bridge” to the October Medium Term Budget (MTBPS), given the world has turned completely upside down since the February Budget. Things are also extremely uncertain, so the projections could change again by October. Importantly, the Minister also announced that the MTBPS would reveal details on a number of initiatives to raise economic growth and reduce debt over time.

Because the economy is expected to contract by 7.2% in real terms this year (and 3% in nominal terms, i.e. before taking account of inflation), tax revenue will be R302 billion less than was projected in February in the current fiscal year. Spending will be R43 billion higher, largely driven by the demands of fighting the pandemic, though the overall increase was reduced through reprioritisation.

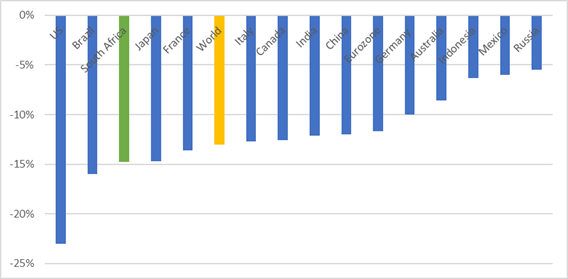

The net result is that the main budget deficit – the difference between spending and revenue – will almost double from the February projection to R709 billion (or 14.7% of GDP). The projected deficits for the following two years are expected at 9.3% and 7.7% of GDP respectively, still much larger than pre-pandemic levels, because it will take the economy until 2021 to return to 2019 levels of nominal activity, according to Treasury’s estimates. It is worth remembering that these deficits are in line with the projections of other countries.

Chart 2: Projected 2020 budget deficit for selected countries, % of GDP

Source: International Monetary Fund

Probably the worst part of it is that almost a third of the deficit (R236 billion in the current fiscal year) will go towards paying interest on existing debt, rather than productive spending. (Though of course this also amounts to a large injection of cash into the hands of bondholders, most of whom are South Africans.)

Increased borrowing

The deficit has to be funded by borrowing. Some $7 billion will come from international agencies, including the IMF, in the form of low interest loans. The government should consider increasing this amount. However, while the initial IMF loan doesn’t come with significant strings attached, additional support would. Such conditions are seen by many in ruling party circles as infringing on South Africa’s sovereignty.

The bulk of the deficit will therefore have to be borrowed in the local bond market, at relatively high interest rates, though the steep yield curve means shorter-dated bonds have much lower yields than longer-dated bonds. As a result, the Treasury does intend to borrow more at the shorter end than in recent years.

All this borrowing in turn means debt will accumulate rapidly. The public debt ratio is expected to jump from 63% last year to 82% next year. Government hopes to introduce measures to raise economic growth and reduce borrowing, so that debt peaks at 87% in the 2023 fiscal year. It also provided an estimate of what will happen if nothing is done. The ratio rises to 100% by 2023 on its way to hitting 140% at the end of the decade. It would be a debt spiral, and the Supplementary Budget makes it clear that government does not want this to happen. Actions speak louder than words, however.

A peak of 87% sounds scary but remember that this expresses debt (a balance sheet item) to a year’s worth of national income. For a household with a R100 000 monthly income and a R2 million home loan, the debt to GDP ratio will be 166%. Unlike a household, a government is essentially an infinitely lived entity. It doesn’t need to pay back the debt, as long as it can roll it over when due and make the interest payments along the way. What matters therefore is maintaining sufficient market confidence to be able to keep rolling over the debt, and earning enough tax revenue to make interest payments and fund essential spending.

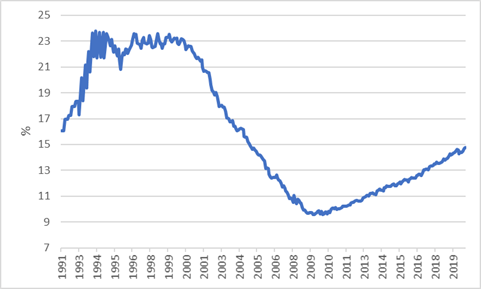

Given high interest rates, it is a tall ask, but we’ve been there before. Interest payments consumed around 20% of tax revenue on average in the 1990s (and in some years much more). In other words, 20 cents in every tax rand collected was diverted to interest payments. It declined to 10 cents on the rand by 2008 as debt and interest rates fell, but then quickly rose to 15 cents by the end of last year. With the collapse in tax revenues this year, it will rise to 21 cents. And it will remain there if all goes according to plan in the next few years. Although this will leave less money for spending in other important areas, it is not a crisis on its own. What will be important is how the remaining 79 cents is spent. There can be no tolerance for waste, and the state needs to be relentless about getting value for money. Crucially, it should strive to maintain a good balance between current spending (wages, transfers, consumables) and capital spending (maintenance, upgrades, new infrastructure).

On this front, negotiations with unions on wage restraints will be critical. One of the more encouraging announcements from the Supplementary Budget is the adoption of zero-based budgeting from October onwards. The budgets for government departments will start at zero every year and they will have to motivate for every rand to be spent. Until now, every year’s spending allocation was basically the same as that of the previous year, adjusted upwards by a few percent. There was no incentive to look long and hard at what is truly necessary.

Also encouraging is that the long list of bailouts for state-owned enterprises could be shortening. There was no additional funding allocated to SOEs, not even to the ‘new’ restructured SAA, although the Land Bank did get a R3 billion capital injection.

Chart 3: Government interest payment as % of tax revenue

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

Confidence and crises

The issue of market confidence is trickier and essentially unpredictable. As we saw in March and April, when foreigners sold R80 billion of bonds and yields spiked, a loss of confidence can come out of the blue. It is usually the result of a global crisis episode, but domestic events can also be the cause, such as Nenegate in December 2015 (though the firing of then Finance Minister Nene occurred against the backdrop of an emerging market sell-off). Both these episodes were short-lived, however.

A complete and sustained Argentina-style collapse in confidence is another kettle of fish. Prudential regulations and capital controls mean that, while foreign investors can vote with their feet, domestic investors have fewer options. But domestic investors can also reach a point where they will no longer want to absorb increasing debt. The warning sign will be when government’s weekly bond auctions start failing. So far, these are still oversubscribed even though the size of the auctions has increased.

Clearly, a key variable in stabilising debt and maintaining market confidence is faster economic growth over time. Trying to close the budget deficit now in the midst of a recession is counterproductive. Substantially higher tax rates and/or deep spending cuts would hurt the economy even more. But when economic activity picks up, we should expect both. Indeed the Minister has pencilled in R40 billion in tax increases over the medium term, starting next year. This is not a massive increase though and does not suggest big tax rate increases or the introduction of new taxes. The intended adjustments to stabilise debt fall 85% on the spending side.

Without being able to throw money at the problem of economic growth, there are only four things the government can really do to release the ‘animal spirits’ of the private sector (as John Maynard Keynes called it) and raise the growth rate post-lockdown.

Firstly, reduce policy uncertainty, including the key areas of mining and agriculture.

Secondly, cut red tape and unnecessary restrictions, including on skilled immigration and tourism visas. Thirdly, just getting the basics right by increasing efficiency, especially at a municipal level: fixing the potholes, speeding up planning approvals, address water and electricity supplies.

Lastly, allow the private sector to participate in areas currently monopolised by SOEs, ‘crowding in’ private expertise and funding, including from foreign investors. To this end, there was a positive announcement last week. A presidential infrastructure summit announced 55 “bankable and shovel-ready” projects have been confirmed without needing to draw on the fiscus. They might require government guarantees, however. There is little on the above list that is under the direct control of the Finance Minister, and the expectation for big reform announcements last week were a bit misplaced.

Where to now for investors?

The big, but somewhat poorly articulated fear of investors is a debt crisis or fiscal cliff. However, a country that largely borrows in its currency has a lot of leeway to avoid such a fate, however you want to define it. Unfortunately, from a socio-economic point of view, there will be less money available for service delivery as more will be diverted to paying interest. There will also be less money available for capital spending, although the government can draw on private spending to fill this gap to an extent.

The biggest risk to any bond investor is a default on the debt – a failure to pay interest or repay capital or both. This remains extremely unlikely. Fundamentally, the problem in South Africa is not that we lack money, but rather that we don’t prioritise well and spend efficiently.

Another risk often touted is that governments here and abroad will seek to inflate away the debt, pushing up inflation to reduce the real value of the bonds. But in a disinflationary global environment, it is not clear that this will be possible, even if this is the intention. Stats SA’s data (collected with some difficulty during lockdown) shows that inflation in April was 3%, the lowest since mid-2005. This puts the real yield on longer-term government bonds in the region of 7%. This is clearly pricing in a lot of bad news and offering a very attractive opportunity, especially now that the real yield on cash has declined substantially. An expected rate cut next month could put the repo rate at 3.5%.

No one will deny that there are risks to South African government bonds, emanating from both local and global sources, and the world remains very uncertain. But we see the asset class as attractive in the context of a diversified portfolio.

At OWLS Software we offer 8000 insurance software features designed to automate any Insurers, UMAs or Brokers insurance admin.