Signal & Strategy Monthly column

James Steere, Head of Operations, Perspective Investment Management

Market timing is not investing, it is guessing. There exists a deeply rooted belief among many investors that with just enough insight they might be able to buy low and sell high. While the logic is sound, doing this on a consistent basis is incredibly difficult, even for seasoned professionals.

Why market timing is a bad idea

It’s extremely difficult to get right – Markets are influenced by so many unpredictable factors: global economic cycles, central bank policies, geopolitical tensions, and more recently pandemics and lockdowns. These forces impact prices in the short term, and most are beyond anyone’s ability to forecast accurately on a consistent basis.

Moreover, in the short run, markets are often driven more by sentiment rather than fundamentals. News headlines and market commentary can create emotional noise that clouds rational decision-making.

Even respected analysts and economists regularly get their predictions wrong. If the experts struggle to get it right, what chance does the average investor have?

It encourages emotion-driven mistakes – All too often, investors are driven by fear and greed. One sees markets rising, and the fear of missing out sets in. One sees markets falling and panic takes over. These reactions are not new. They are the same human impulses that drove investors in the 1920s to chase “sure things” and abandon them just as quickly when prices collapsed.

Peter Lynch noted that unprepared investors cycle through three emotional states: concern, complacency, and capitulation. Concern arises during market dips (when they should be buying), complacency grows during rallies, and capitulation occurs when fear finally forces them to sell during a crash, often at the worst time.

Empower Your Decisions by Streamlining Your Data

With BARNOWL Insurance Data Warehouse: The Ultimate Data Solution for the Insurance Industry in South Africa.

For more information on how to empower your decisions by streamlining your data, visit bds.co.za

The risk of missing the best days – One of the greatest dangers of market timing is being out of the market during its best-performing periods, which often occur shortly after the worst.

Over the 40-year period from 1985 to 2025, the ALSI delivered a return of 14.1% p.a. (6.0% real). However, if an investor missed just the 10 best-performing months, that return would have dropped to 10.5% p.a. (2.7% real), a massive difference for only a few missed opportunities.

Markets move quickly. If investors are not invested when the rally begins, they may lose out on a significant portion of long-term growth.

Even being half right can be costly

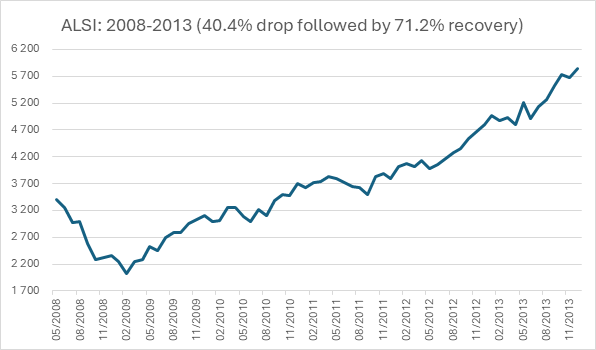

Let’s consider a real-world scenario: Suppose an investor had the foresight to sell out of the equity market in May 2008, just before the Global Financial Crisis. They moved their investments into a money market fund and stayed there for the next five years.

Their returns in the money market would have been a respectable 7.3% p.a.

But if they had stayed invested in the ALSI despite the 42% crash, their five-year return would have been 8.9% p.a., higher than the “safe” choice. And that’s before accounting for the higher taxes typically paid on money market interest income.

The reality is: even if they timed their exit correctly, it’s extremely difficult to time their re-entry just as well. And missing that bounce-back can be more damaging than the downturn itself.

What investors can consider doing instead

Spread out investments – If they’re investing a lump sum, consider spreading it out over several months. This reduces the risk of investing everything just before a downturn and smooths their entry into the market.

Take a long-term view – Short-term share prices are driven by popularity and emotion, but long-term investment returns reflect growth in real business value and cash earnings.

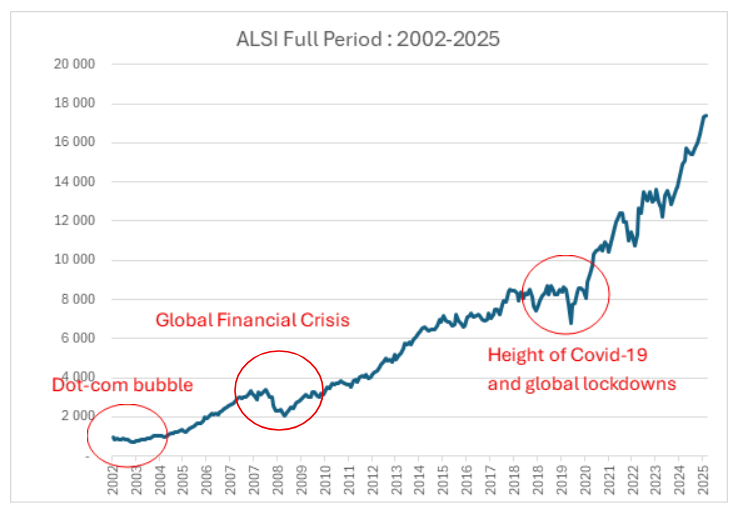

Over the past 23 years, the JSE ALSI has delivered an excellent compound annual nominal total return of 13.4% despite going through three world market crashes and dealing with significant local challenges like low economic growth, the failure of almost all SOE’s, load-shedding, and political instability.

Even zooming in on specific market crashes over this period, which can look terrifying at the time, these events fade into the background over the long run.

Take the graph below as example.

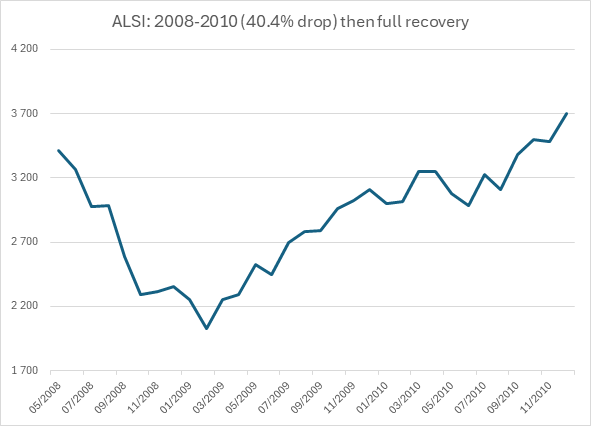

The 2008 global financial crisis, shown in the graph above, was a particularly frightening time for investors. Many believed that this time was different, with major banks and entire economies collapsing and no recovery in sight. Yet, it took just 30 months for the JSE to return to its pre-crisis levels. Once the market recovered, it didn’t stop and began to gain strong momentum. This growth would have been missed by any investor who panicked and sold during the crash – easier said than done!

Importantly, there hasn’t been a single 5-year rolling period in the past 40 years where the ALSI has delivered a negative annualised return. That’s a powerful case for staying invested.

Only invest what you can afford to leave invested

Investing in equities should be for money an investor doesn’t need in the short term. This provides them the advantage of keeping calm, sitting on the sidelines, and doing nothing during market downturns, without being forced to sell which often locks in losses unnecessarily.

Conclusion

Trying to time the market is not just difficult, it’s risky, emotionally draining, and statistically proven to reduce returns. Instead, a more effective strategy is to stay invested, remain diversified, and keep a long-term Perspective (pun intended).

The power of compounding, combined with the natural upward momentum of well-managed markets, is a force that works best with patience and consistency.

In investing, time is the investor’s greatest ally, not timing.