Renier De Bruyn, Investment Analyst at Sanlam Private Wealth

Economists are predicting that worldwide, the pace of economic decline resulting from government actions to stem the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be worse than it was during the global financial crisis of 2008/09.

No one can deny that the consequences for the South African economy will be dire. Like other industries, our banking sector will be negatively impacted. However, the banks are well capitalised to withstand a material deterioration in the environment relative to previous crisis periods. With banking share valuations at historic lows, we view the future return prospects of the sector quite favourably.

At the time of writing it is unclear how long the COVID-19 lockdowns in countries worldwide will continue. As the number of active cases of the disease starts peaking in early hotspots and governments consider the economic costs of the most stringent countermeasures, we can expect announcements of some relaxation of these measures over the next few weeks. The longer the lockdowns last, the greater the likelihood of permanent economic damage arising from job losses and business insolvencies that would make a swift economic recovery more difficult to achieve.

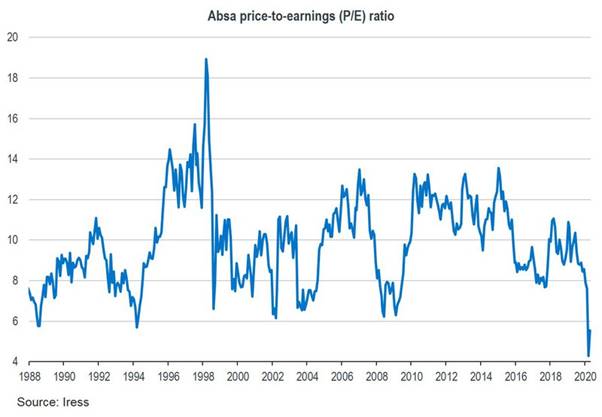

Banking shares globally have been particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 market sell-off, and our local banks have not escaped the pain. By 30 March, the FTSE/JSE Bank Index had lost 47% of its value since the start of the year, before recovering somewhat over the past two weeks. On most valuation metrics, our banks are now cheaper than during any period over the past 30 years – including the 1997/98 Asian banking crisis and the 2008/09 global financial crisis (GFC). Some of my colleagues have even referred to former President PW Botha’s 1985 Rubicon speech in an attempt to find a period of comparable valuation. As an example, the chart below shows the historic price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of the Absa Group:

Chart 1

Rising bad debts

Banks have the benefit of deriving most of their revenue from annuity-based sources, such as their loan books and transactional account bases, and have been allowed to continue operating during the lockdown. While the economic fallout of COVID-19 will certainly impact their revenue bases negatively, they may – from a top-line perspective – well be more resilient than most other industries in South Africa.

However, banks are intricately linked to the credit health of households and businesses, so they’re likely to experience materially higher bad debts over the next year. Furthermore, the 1.25% cut in the South African Reserve Bank repo rate between January and March, with a further 1.00% cut this week, will have a negative impact on banks’ net interest margins.

With banking share valuations at mouth-watering levels, the market is likely to be concerned about the ability of banks to survive the current storm of rising bad debts from a capital perspective, given their leveraged balance sheets. It’s still too early to confidently forecast the extent of the bad debt issue for banks, and given the uniqueness of the situation, we don’t have any historical period to use as a yardstick.

We can, however, ‘stress test’ the banks’ capital adequacy ratios under different bad debt scenarios. Our calculations show that their credit loss ratios need to rise by approximately eight times from last year’s base, or around four times the level during the GFC, before their capital levels decline to minimum regulatory requirements.

Greater capital strength

The GFC left a significant mark on the global banking sector, and to ensure a more resilient industry during future crises, regulations have been tightened over the past decade. In particular, banks have to hold higher levels of capital, own more high-quality liquid assets and carry higher levels of provisions than they did previously. Banks have also scaled down their exposures to the market risk carried on their balance sheets.

COVID-19 will be an important litmus test for the resilience of the banking industry in a crisis under tighter capital rules. However, banks are entering this crisis with more capital strength than was the case during the GFC, and central banks have responded very early to support the system.

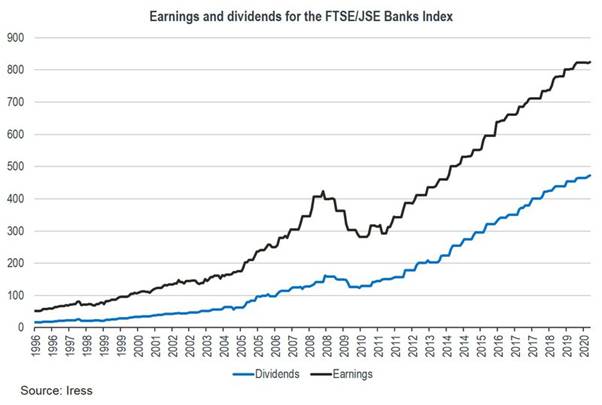

South African banks proved their resilience during the GFC, surviving without taxpayer assistance and continuing to pay dividends to shareholders. While the earnings and dividends of local banks fell by around 30%, they recovered well in the years after the GFC, as can be seen on the graph below:

Chart 2

Trading opportunities

South African banking remains a concentrated industry, dominated by a few rationally behaving and well-regulated private sector companies with scale advantages and brand trust. The market structure is therefore conducive to appropriate profitability, and our major banks have indeed delivered returns on equity consistently above their cost of capital over the past decade, despite an unsupportive economy at most times. Their share prices, however, have been subject to high levels of volatility, driven by fluctuating investor attitudes towards the local economic and political landscape. This has created a number of trading opportunities for valuation-driven investors.

In conclusion, while we expect COVID-19 will have severe consequences for the South African economy in 2020, our banks are well capitalised to withstand a material deterioration in the environment when compared to previous crisis periods. With valuations at historic lows, we are cautiously optimistic about the future return prospects of the sector, and are selectively adding banking shares to our clients’ portfolios.