Izak Odendaal and Dave Mohr, Investment Strategists, Old Mutual Wealth

The dictionary definition of a dilemma is a difficult choice between two options, often a choice between unpleasant options.

The obvious big dilemma of the moment is the one facing governments around the world: the choice between ending lockdowns and potentially allowing the coronavirus to spread unimpeded, or to maintain lockdowns and cause untold economic damage.

However, most serious thinkers will argue that in this case it is not a matter of choosing the one or the other. Simply ending all corona-related restrictions will not result in an economic boom. Consumers are likely to be too cautious to return to old spending habits, while many workers will be reluctant to return to their posts while the virus is still spreading. Similarly, to argue that we should maintain strict lockdowns to save lives ignores the fact that poverty and unemployment are also deadly. The key is to find a balance between allowing as much economic activity as possible while maintaining effective social distancing. Easier said than done, of course.

Global equities: a bounce too far?

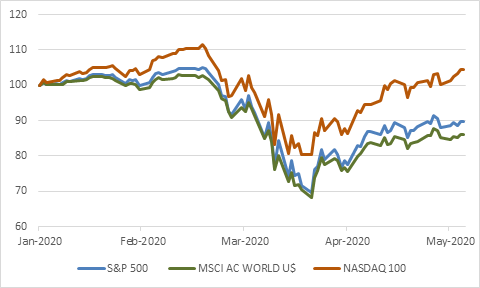

South African investors also face at least four dilemmas. The first is whether or not to trust the rebound in global equities. Given the economic carnage, the equity market response has not been nearly as bad as history would suggest. The MSCI All Country World Index is only 13% lower than at the start of the year. In rand terms, it is positive.

Chart 1: Global equity rebound

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

But then again, this is not a normal global recession. It was caused by governments deliberately shutting down large parts of their economies. Reopening should end the recession, but it is still not clear how soon this can be done with confidence.

We also need to ask how much lasting damage is being done? Many businesses will disappear forever, and many people who lose their jobs will struggle to find new ones, with all kinds of long-term negative implications.

To give just two recent examples of the extent of the economic damage: The official US unemployment rate shot up to 14.7% after a record 20.5 million Americans lost their jobs in April. In South Africa, only 105 new passenger cars were sold countrywide in April, a fraction of normal sales levels. You could argue that car-buyers can easily wait a month or two, but the dealerships might not survive that long.

Then there is the unknown of behavioural changes. If households decide to increase savings and businesses increase cash holdings as a buffer against future shocks, it will mean lower spending levels. Some industries that rely on putting large groups of people in a confined space (conferences, airlines, concerts, movie theatres, restaurants) may take years to recover, or may need to reinvent the way they operate.

What is also different this time round is the extent of the fiscal and monetary policy response. This has taken worst-case scenarios off the table, but whether it results in a strong economic rebound remains to be seen.

Usually the best guideline is valuation. When the market is cheap enough, there is a margin of safety even if things don’t turn out quite the way you thought they would. However, the uncertainty is so great – again because this is not a normal recession – that traditional valuation metrics might not be telling us much. The trusty old price-earnings ratio depends on having a reasonable idea of what earnings will be for the next year. We clearly don’t.

Still, if we take them at face value, global equities are not cheap. The MSCI All Country World Index trades at a forward price: earnings ratio of 17 times, the highest level since 2004. This is largely due to the expensive US market, which trades at 20 times forward earnings. Excluding the US, global stocks are trading at 14 times, which is average, but not cheap.

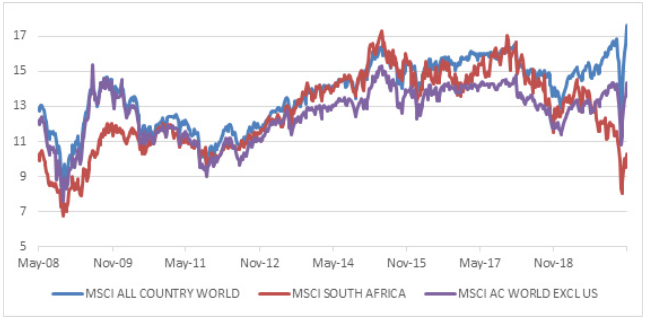

Chart 2: Global and local equity forward price: earnings ratios

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

US equities have rallied more than others largely because of the mega tech companies. The tech-heavy Nasdaq index is already in positive territory year-to-date. This makes sense, as these companies clearly benefit from our collective shift from offline to online. That’s great if you already own them, but it is not clear whether it makes sense to buy them now.

It seems that even the great value investor Warren Buffett, he of “be greedy when others are fearful” has not found bargains, despite the market crash. Instead, he has disposed of his stakes in airlines. Clearly others are not fearful enough for his liking.

However, with short and long-term interest rates extremely low in developed countries, many investors lack alternatives. Even with anticipated dividend cuts, you can still earn more income from a large-cap equity portfolio than from developed market government bonds. This has to be factored in.

Local is cheap but risky

The second big dilemma is South African equities. For many of us, this asset class looms large because Regulation 28-compliant funds rely on it to drive long-term returns. South African equities experienced a bear market along with its global peers, but did not enjoy the preceding bull market. Local indices moved sideways in the years prior to the corona crisis.

Unlike global stocks, the local market looks cheap relative to history. The difficulty is that the local economic outlook is cloudy, to say the least. The knock to the South African economy is on a par with what other countries are experiencing. The difference is that we came into the crisis on a much weaker footing, already in recession. Our ability to respond from a policy point of view is also much more limited with excessive government borrowing prior to this crisis. Unless there are deep (but unpopular and therefore unlikely) policy reforms, there is no reason to expect the local economy to perform better than the global economy in the next few years. Added to this, the local market with a hundred or so shares is much more concentrated than the global universe of thousands of companies.

And unlike in global markets, you cannot make the case that low interest rates support equity valuations. South African long-bond yields remain elevated, though they are lower than they were when Moody’s downgraded South Africa to junk status. The Reserve Bank’s tentative intervention in the bond market might have contributed. It bought R11 billion in government bonds in April according to its latest balance sheet data, taking its total holding to 0.4% of GDP, a fraction of what developed market central banks have done. It should be doing more, and long elevated yields blunt the impact of its short-term cuts.

Reckoning with the rand

An additional dilemma for South African investors is overall offshore exposure. The rand remains close to record lows against the dollar and other major currencies. Is it a good time to bring money back? Or should you take more overseas given the local outlook? There are four considerations to remember.

The first is that we know that the rand recovered from blow-out episodes in 1998, 2001, 2008 and 2015. Secondly, in the short term it is extremely volatile and timing its turning points extremely difficult. Thirdly, the long-term depreciation trend should remain in place, as our economy is less competitive than our major trading partners. Lastly, while the rand can boost or detract from global returns in the short term, the decision about offshore allocation needs to be determined by the assets you are buying and selling, with the exchange rate a secondary consideration.

Chart 3: Rand-dollar exchange rate

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

Should I stay or should I go?

The final dilemma is for conservative investors. The Reserve Bank’s repo rate reductions will provide financial relief for many, but for others it will substantially reduce returns from low risk investments. This is at precisely the time when many investors have switched into these vehicles. Morningstar data show that South African money market unit trust funds swelled from R6.7 billion at the end of February to R7.6 billion at the end of April (this obviously excludes bank deposits, guaranteed products and other low-risk vehicles). It chimes with what we’ve seen globally. Swiss Bank UBS estimates that global investors have increased investments in various money market vehicles by $1 trillion in the past two months (to a total of $4.7 trillion). Bear in mind that most of this money is earning close to zero returns, often negative after fees, tax and inflation.

High real short-term interest rates of around 2% to 3% in the past few years meant investors in local money market funds did not have to face a trade-off between risk and return. They will now have to weigh up the pros and the cons of staying put or moving into higher risk investments with potential upside but also potential downside. This is a decision best made in consultation with a financial planner.

No easy answers

There are no easy answers to these issues. Investing, it is often said, is simple but not easy. Simple, because we all know we should buy low and sell high. Difficult, because we don’t always know when something is high or low, while our emotional state often argues against selling when markets are up, and against buying when they are down. With the current uncertainties it is ten times worse.

Our approach continues to be to try to balance all these various risks and trade-offs rather than to make forecasts about the future and then bet the farm on them. While it sounds like a stuck record to talk about the importance of diversification in these uncertain times, it remains true.